Lieve Edith,

Hoe kon ik nou vergeten dat jij het geluid van gillende bommen, op de gekste momenten afgevuurd vanuit de eigen of vijandelijke vuurlinie, al meer dan een kwart eeuw kende? Ik stel me dat zo voor. Je vrijwillige bijdrage aan het Rode Kruis. Na het vrolijke gefluit van granaten en bommen. In het rusteloos pauzerende niemandsland waar geen soldaat zich durft te wagen verzamelen jij en je medezusters allerhande ledematen - losse onderdelen, vingers, onderarm, bovenarmen, nog hele armen, met hand en vier vingers, alleen de duim mist de vingers enorm - rompen, met of zonder ingewanden, rondslingerende darmen, bonkende harten, losse longen die de allerlaatste keer hun adem uitblazen, levertjes, niertjes, volledig verdwaasde hoofden die hun rompen zoeken, als er nog een oog in de kas zit op rond te kijken. Wat vergeet ik Edith? Benen en voeten. Raap je ook de briefjes op, de foto's, de kettinkjes? Die gaan ook terug naar moeder, naar vader die te oud was voor deze oorlog. Ik vergat het scrotum. Dat in de prille liefde de moeder zoekt die het zo graag had willen verwekken. Nageslacht is troostrijk. Het kan de volgende oorlog voeden.

Let even op de continuïteit Edith, wil je? Ik steek veel tijd in de brieven aan Dolf. Er hangt zoveel van af dat hij naar de kunstacademie gaat. - Dat ik dat zeg is niet bepaald origineel, eerder flauw. Honderdduizenden geleerden hebben zich dat voor mij ook al zitten afvragen. Lelijk Nederlands. - Ik geloof niet dat het waar is dat je als je Hauptbahnhof uitloopt meteen links of rechtsaf moet slaan om bij dat foeilelijke sektarische gebouw van de Sezession te komen, maar dat geeft niks. Ik denk dat hij, Dolf, toch niet gaat, te lui als hij soms is. Ook leest hij slecht is mijn stellige indruk. Hoe het ook zij, mocht hij de brief wel goed lezen en ook daadwerkelijk van Linz naar Wenen reizen en hij slaat de verkeerde weg in, een deel van de mensen op straat kan heus wel Duits. Ook hoeft hij echt niet bang te zijn om door elke Jood of Hongaar beroofd te worden. De meeste mensen deugen.

De Kus moet Dolf echt gaan zien, het is niet lelijk maar ook niet bepaald mooi. Of er momenteel ook werk van Schiele hangt, waag ik inmiddels te betwijfelen. Ik dacht er tijdens dat onweer van gisternacht over na en begon aan de onfeilbaarheid van het geheugen te twijfelen. Dolf en Egon zijn toch van dezelfde generatie? Mijn oma en die van Mijn Vriend zijn van dezelfde generatie en komen uit dezelfde buurt. Rondom 1890. Dolf is van 89. Egon van hetzelfde laken een pak of een jaartje jonger of een jaar ouder. Toch? Kijk het even na Edith, het zou vervelend zijn. Ik weet heus wel dat Schiele op de Weense kunstacademie zat. Misschien meldden beide van Lebensraum zwangere jongens zich wel tegelijkertijd aan? In 1907? Of in 8? Laat ik de gok wagen.

Wolfsschanze I Die Niederlände I Juni 2025

Beste Dolf,

Leuk nieuws! Via via - via mijn oma van vaders kant die min of meer uit dezelfde streek komt - ken ik een jongen die gelijk met jou toelating wil doen aan de academie in Wenen. Ook hij mikt zo hoog mogelijk, slaat alle lokale, lees provinciale, academies over om gelijk de Donau over te steken op weg naar de hoofdstad van het keizerrijk. [Edith: Of het waar is dat je vanuit Tulln waar Egon woont ook echt de Donau over moet weet ik niet, maar het klinkt mooi.] Jullie hebben zowat dezelfde drive. [Hoe zeg je dat netjes, Edith, als je dat Engels waarmee onze moerstaal mee wordt bezwangerd aborteert? Begeestering?] Jullie kunnen allebei goed tekenen. Komen allebei uit de stad, in ieder geval niet uit een in de tijd achtergeleven dorp. Jullie spreken allebei goed en verstaanbaar Duits, als je Duits kunt.De jongen over wie ik het heb heet Egon Schiele. Ik denk niet dat je hem kent. De wereld is niet zo groot maar ook niet klein. En Oostenrijk-Hongarije lijkt samen met Duitsland en nog wat landelijke gebieden veel op goudhaartje: niet te groot maar ook niet al te klein. Mocht je Egon kennen, dan is het kat in het bakkie. Dan kunnen jullie elkaar bellen om wat af te spreken. Durf je dat niet goed, schrijf dan zijn oma een nette brief zoals je vader dat zo goed kon. [In het Duits is dat anständig Edith, ik weet niet of je dat wist.]

Ik kan me vergissen, maar als ik het goed zie, dan zijn jullie allebei goede klassieke tekenaars, maar de voorlopige toekomst ligt in het loslaten van de nabootsing van dat wat de ogen zien als ze normaal uit hun ogen kijken. Er komt een tijdperk aan, ook voorlopig, waarin de objectieve wereld geen macht meer uitoefent over het subject. [Had ik het eerder in de tijd niet ook al over subject versus object Edith? Dan moet het er hier uitgehaald.] Wat onze ogen zien weten we onderhand maar al te goed, wat de ziel ziet weet niemand. In de filosofie is er al een flinke stap gezet in de richting van de mens die zichzelf losweekt van de oude wijnfles waar ie op zat geplakt als een onbeweeglijk willoos etiket. Niemand dicteert ons de werkelijkheid langer dan vandaag, god is de verschaalde rode wijn wiens bloed moet vloeien over tot op de bodem van de leeggedronken fles. [Is dit beeld correct?] Er is geen andere schepper van het noodlot dan de mens zelf.

Een aanrader zijn ook de opera's van Richard Wagner. Als jouw vader van Duitse muziek hield, had hij vast een grammofoon in huis en een paar platen. Je kunt het aanzetten als je tekent. Zet het geluid niet te hard. Je hoeft niet steeds te luisteren. Het duurt erg lang allemaal. Maar iets dringt diep in de ziel. Het gaat om Germaanse helden die boete doen en zo hele volkeren verlossen, het liefst Germaanse stammen. Wagner was ook bevriend met de jonge Duitse filoloog die je eens moest lezen maar wiens naam ik ben vergeten. Ze zijn allebei al jaren dood. Ze kregen ruzie. Grote geesten kunnen niet goed naar elkaar luisteren. Dolf, ik raad je aan zelf je lot in handen te nemen en het aan niemand anders over te laten. Er is geen verlossing dan zelfverlossing:

Het zou echt mazzel zijn en tof Dolf, wanneer jij en Egon in dezelfde klas kwamen en les hadden van dezelfde professor. Doe een paar maanden mee met gipstekenen, laat zien dat je veel goede zin heb en de beste wil. Wees aanvankelijk niet lui. Zorg voor rust, reinheid en regelmaat in het tekenen: drink niet teveel, zorg dat je handpalm het tekenpapier nier raakt en teken elke dag. Goethe zei: 'In der Berschränkung zeigt sich erst der Meister.' [Controleer het geslacht even.]

Als het jullie gelukt is een paar klasgenoten op te stoken, kun je de professor confronteren met zijn kinderachtige lessen uit een archaïsch en het achterhaald tijdperk. Verwijs naar de enorme vooruitgang die Klimt en consorten hebben geboekt, strooi, als hij te weinig krimp geeft, met een paar grote namen uit de psychoanalyse en als alles tegen blijft zitten, dreig met de klassenstrijd. Per slot van rekening horen noch Egon noch jij bij de walgelijk imperialistische elite die kolonie na kolonie sticht op plekken waar nooit witte mensen waren. Dat jullie uit een iets hoger milieu komen dan een laag boeren of arbeidersmilieu moest je maar gewoon zo lang mogelijk verzwijgen.

Schrijf me eens gauw terug, Dolf, ik zou graag je gedachten eens lezen.

Hartelijks Joseph Heij

Je zult het niet eens zijn met mijn adviezen Edith, maar ik zie niet hoe ik het anders moet inkleden.

Liefs Joseph

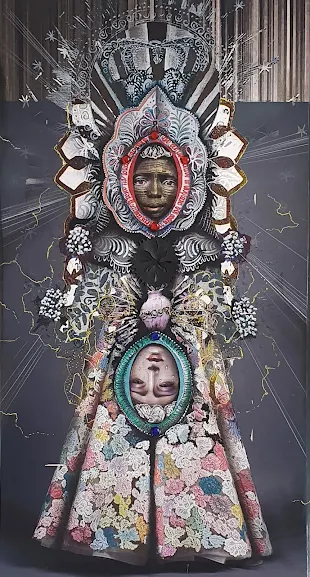

NB Ik ben bezig met een nieuw werk voor mijn vriend en zou graag jouw mening eens horen. Er staat een aanstootgevend naakt meisje op omringd door menselijke foetussen. In haar buik heeft ze nog een extra embryo, maar dat is anatomisch opengesneden. Het weefsel zwemt in een fles sterk water en is bedoeld voor wetenschappelijke doeleinden. - Jammer dat je zoiets nooit ziet op Marktplaats. - Het gaat me er niet om of je het mooi of lelijk vindt, ook niet of het knap is getekend; het gaat om wat jij denkt dat het betekent zonder dat je beschikt over enige voorkennis. Wee dus alsjeblieft zo objectief mogelijk, wil je?